by Guest Blogger BitcoDavid

The title of this piece is actually a quote by Justice Hugo Black, as he wrote the majority opinion in the case of Gideon v. Wainwright, on March 18, 1963 – an opinion, and a fundamental right, seen as so important to that Supreme Court, that they were unanimous in their decision.

Clarence Earl Gideon was brought up on charges in Florida, for breaking and entering. He could not afford an attorney. At the arraignment, he asked for a Public Defender, but was refused. Instead, he was told that the court was only mandated to provide counsel in capital cases. Gideon ended up serving 5 years.

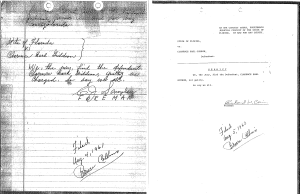

Gideon – by himself and from prison – appealed, pleading his case on Florida State Prison letterhead – in pencil – and utilizing law books from the prison library. As defendant in his suit, he named the Secretary to the Florida Department of Corrections, H.G. Cochran. By the time the case was heard, Louie L. Wainwright had replaced Cochran. Gideon successfully argued that his 6th and 14th amendment rights had been violated. His attorney, assigned him by the SCOTUS, would be none other than future Supreme Court Justice – Abe Fortas.

Gideon – by himself and from prison – appealed, pleading his case on Florida State Prison letterhead – in pencil – and utilizing law books from the prison library. As defendant in his suit, he named the Secretary to the Florida Department of Corrections, H.G. Cochran. By the time the case was heard, Louie L. Wainwright had replaced Cochran. Gideon successfully argued that his 6th and 14th amendment rights had been violated. His attorney, assigned him by the SCOTUS, would be none other than future Supreme Court Justice – Abe Fortas.

Upon receipt of this ruling, a new trial was held, and in it, Gideon was given an attorney. He was acquitted in his second trial. Had he had competent legal council in his first trial, he may never have had to serve time at all.

But, a lot has changed since 1963.

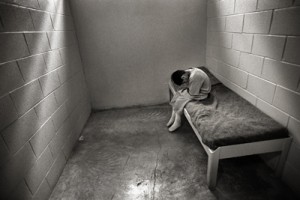

Where the necessary evil that is prison, existed once to serve society – and the justice system was built around an effort to keep innocents out of incarceration – we now have a prison industry that views the public as grist for its mill – fodder for its filthy lucre. States weigh the costs of providing justice against the profits of warehousing human beings.

Several paradigms have shifted since Gideon. We now have a War on Drugs complete with mandatory sentencing, gang activity, multinational military incursion and a gun lobby that relishes arming both sides in the conflict. We have the largest narcotics consumption rate in the entire world, and at the same time we fund and arm nothing short of military juntas to enforce drug laws.

We now have a war on poverty – not LBJ’s idyllic Great Society – but rather, a war on the poor, themselves. Taxpayers, suffering under the yoke of a broken economy can no longer justify paying for the needs of those less fortunate. It’s a tough row to hoe, for a politician during a close race, to ask for tax dollars to provide legal defense for criminals, especially indigent, drug addicted ones.

We now have a largely privatized prison system, which can only function when beds are full. These companies spend vast sums on lobbying legislators to pass more and more draconian laws, more and more mandatory sentences and more and more budget cuts in terms of legal defense and public civil liberties.

And, of course – as if we’re not fighting enough wars – there’s the good ol’ War on Terror. Nowadays, it doesn’t require flying jets into buildings to be labeled a terrorist. You can have a penchant for typing too much on your computer. You can try your hand at flash-mob type civil disobedience, or you can simply join a group of likeminded activists who want to rescue companion animals.

Our society has turned more punitive and more afraid, while at the same time our coffers are now bare. States are commonly seeking out ways to kneecap the Gideon ruling. In the end however, we lose. Deny America’s promise of justice to one, you deny justice to all.

_________________________________________________________________________________________________________

BitcoDavid is a blogger and a blog site consultant. In former lives, he was an audio engineer, a videographer, a teacher – even a cab driver. He is an avid health and fitness enthusiast and a Pro/Am boxer. He has spent years working with diet and exercise to combat obesity and obesity related illness. He can currently be found, pounding away on the keyboard at DeafInPrison.com and BitcoDavid’s BoxingBlog.

- Oyez Project (listen to the oral argument).

- Gamso: An Obvious Truth

- Greenfield: The Silence of Gideon

- Bobby G. Frederick: Happy Birthday Gideon

- Windypundit: 1-800-LAW-REP-4

- NYT: Gideon’s Muted Trumpet

- The Guardian: Why it’s one law for the rich in America and McJustice for the rest

- Stephen B. Bright and Sia M. Sanneh: Fifty Years of Defiance and Resistance After Gideon v. Wainwright [PDF].

- Second Class Justice: 50 years after Supreme Court declares lawyers are constitutionally required, the right to counsel is violated every day in criminal courts

- Connecticut Law Tribune: Public Defender Resigns Over Lack Of Resources