I’m excited that West Virginia University is starting a book group that seems based, in part on Changing Lives Through Literature. I have written about CLTL

here and there’s info on

my blog about it as well. When I went to a conference last year in West Virginia, I talked about CLTL and lo and behold, I think it helped Katy Ryan get this group going, although she had been doing great things already with literature and writing behind bars.

This is a press release from WVA. I forgive them the use of the word, “inmate.” For more info, contact: Devon Copeland, Devon.Copeland@mail.wvu.edu _______________________________________________________________

For the past 10 years, community and West Virginia University nonprofit organization the Appalachian Prison Book Project has helped imprisoned people discover the transformative power of reading.

The project began in 2004 after Katy Ryan, associate professor of English at WVU, realized the state did not have any prison book projects.

The group has received more than 20,000 letters from imprisoned people expressing how needed — and essential — reading is. Books have been shipped to men and women in West Virginia, Virginia, Maryland, Ohio, Kentucky and Tennessee.

Now, the program is starting its next chapter – a prison book club in the secure female facility at the U.S. Penitentiary Hazelton in Bruceton Mills, West Virginia.

The idea for the book club grew from a discussion at last spring’s Educational Justice and Appalachian Prisons Symposium, an event co-sponsored by the Appalachian Prison Book Project. Longtime members of the project Cari Carpenter, Elizabeth Juckett and Katy Ryan are facilitating the book club.

“Prisons are built to isolate and to separate. They stand as formidable barriers between those inside and those outside. Books can lessen that isolation,” said Ryan, founder of the Appalachian Prison Book Project. “Malcolm X wrote that reading in prison changed forever the course of his life. ‘It awoke in me some long dormant craving to be mentally alive.’ We all need that intellectual and creative stimulation, and people in prison have fewer opportunities for it.”

Through reading and discussion of selected works, the group hopes to strengthen members’ analytical and communication skills, and build positive peer support and vital connections between people inside and outside prisons.

It can also foster relationships and help mend those affected by incarceration.

“One woman told us that after reading Natalie Goldberg’s Writing Down the Bones, she wanted to reach out to her son. He is going through a hard time, and she hadn’t been able to find a way to connect with him. She had not felt comfortable writing to him, but the book helped her find a way to start,” Ryan said. “She wrote her son a letter. Then they talked on the phone for the first time in seven months.

For others, it can simply be a more personal feeling.

“Several (prisoners) have talked about how a book has stayed with them and given them a new perspective or strength,” Ryan said. “The importance of reading and access to an education while inside prison certainly extends to life outside prison. Studies repeatedly conclude that those with a higher education do better once released than those without. But learning also matters while people are still in prison. Their lives, their health, their relationships, their mental faculties are not on hold. Books—and especially being able to talk with others about books—can be a real resource for living, for figuring things out.”

Every other week the book club works on creative writing. The 14-member group writes short essays and poems, reading them to one another.

“We want the book club to be flexible and responsive to the needs and ideas of participants,” Ryan said. “The women are highly motivated and dedicated to their education and growth. It’s a phenomenal group.”

Though it always accepts donations for postage, supplies and other books (including dictionaries), the group is currently seeking donations of the following titles for the book club. All donated items must be paperback.

There Are No Children Here, by Alex Koltowitz

A Lesson Before Dying, by Ernest Gaines

The God of Small Things, by Arundhati Roy

The New Jim Crow, by Michelle Alexander

I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings, by Maya Angelou

Beloved, by Toni Morrison

Discussions in the club have been fantastic and reaction to the group has been positive, Ryan said.

“Staff members (at the prison) have reached out to let me know that the women are really excited about the program and are talking about the books as they are reading them. And we know that other women are already interested in joining the next group. There is a lot of momentum.

The group says studies show rates of repeat offenses drop when inmates are given access to such materials while inside. The power of the written word, Ryan said, has the ability to change and transform.

“We often describe books as an ‘escape’ or ‘transporting’ — they move us — and yet they return us to ourselves and our moment,” she said. “The right book at the right time can adjust, even alter, the way that we think about life and the world.”

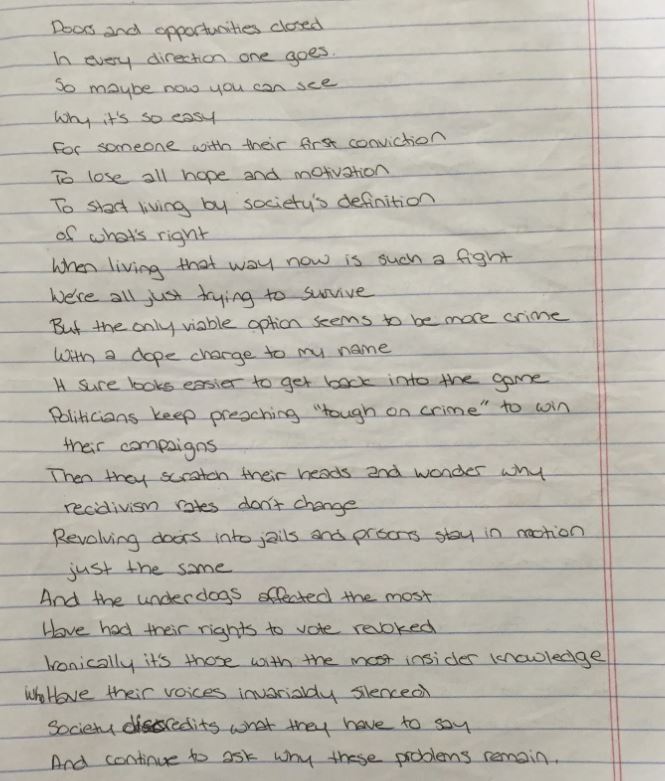

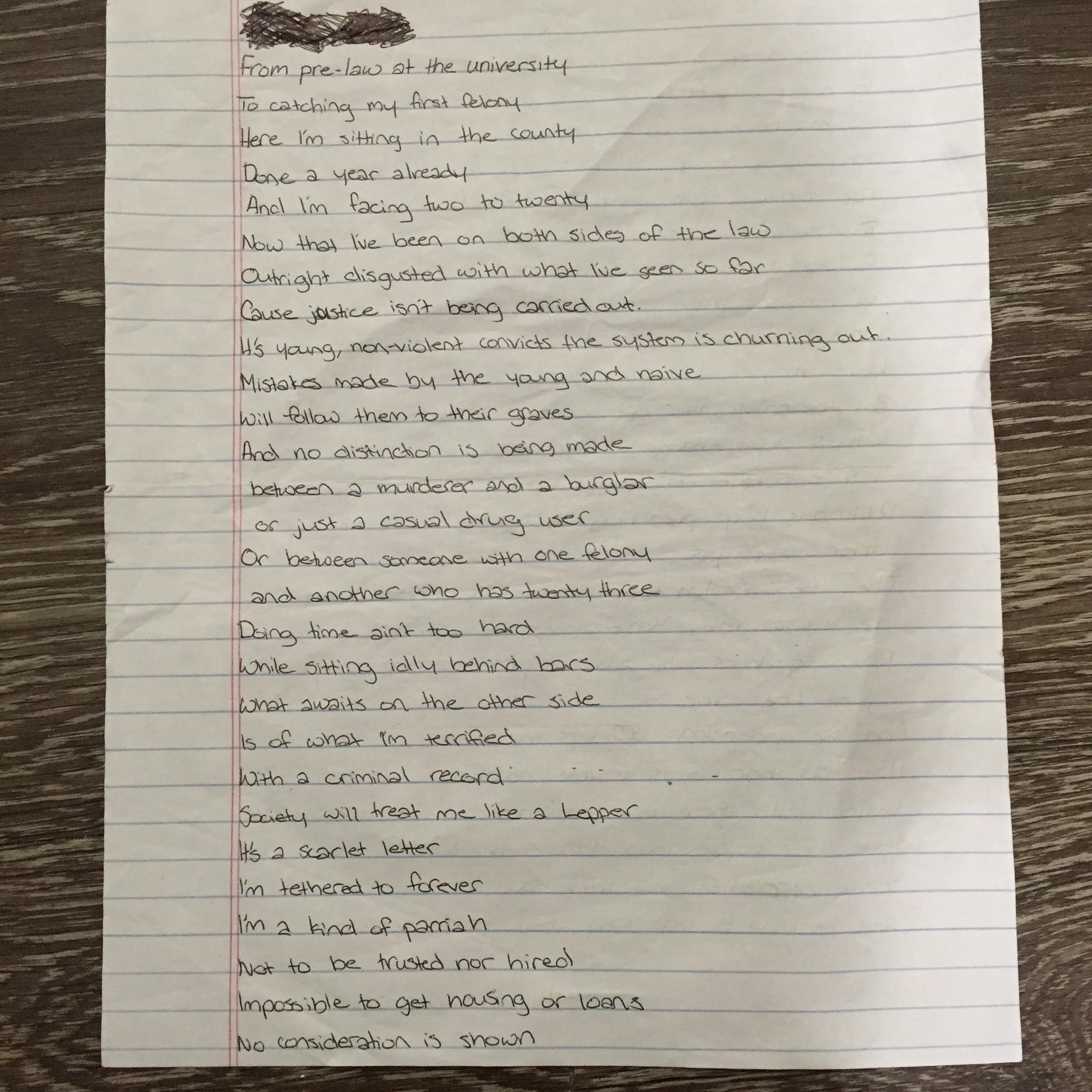

It’s touching to see how she felt like she had a “scarlet letter” even after a year, how she knew what lay ahead was terrifying, and how there was nothing but warehousing going on for her drug habit.

It’s touching to see how she felt like she had a “scarlet letter” even after a year, how she knew what lay ahead was terrifying, and how there was nothing but warehousing going on for her drug habit. But perhaps my favorite of her poems is this one. She realizes what heroin has done to her young life. “I’ve been locked behind bars and time has been murdered.”

But perhaps my favorite of her poems is this one. She realizes what heroin has done to her young life. “I’ve been locked behind bars and time has been murdered.”