Robert Silva-Prentice who is a prisoner at Souza exposes his burns from tasers. Photo courtesy of Attorney Patty DeJeuneas

Robert Silva-Prentice who is a prisoner at Souza exposes his burns from tasers. Photo courtesy of Attorney Patty DeJeuneas

If you were one of the few rows of people who packed into Suffolk Courthouse in downtown Boston on Wednesday, Feb. 19, you heard two entirely different versions of the recent lockdown at Souza-Baranowski Prison in Shirley, Massachusetts. Family members, formerly freed prisoners, DOC officials, attorneys, and press were there to hear these two tales. And to my way of thinking, one of these stories was particularly suspect.

To hear it from the day’s Department of Correction (DOC) spokesman, Pat DePalo Jr., Assistant Deputy Commissioner of Field Services, it was absolutely necessary for a tactical team with helmets, tasers, pepper spray, and dogs, to come into Souza and reorganize the north and the south parts of the institution. According to him, and to Souza Superintendent Stephen Kenneway (who honed his skills at Abu Ghraib), it was necessary to reorganize the entire institution after January 10th, as DOC lawyers said their “intel” had told them there could be rapes and murders of guards and possibly hostages taken. Souza officials said their solution was a lockdown which included transfering 23 prisoners out, rearranging the institution, taking property, and stopping visits, mail, email and attorneys from seeing their clients.

While the attack by prisoners on a correction officer on January 10th was indeed violent, no one has yet to ask WHY the prisoners engaged in such violence. Instead, it as if the DOC does not have to take responsibility for an officer’s behavior. The assumption seemed not to be that an officer was homophobic or brutal or violent to prisoners–which may or may not be true. But instead of inquiring and making public the behavior of that officer who may have provoked violence, the official word is that it was the fault of the Latin Kings, it was a gang fight. In other words, the fault lies in the fact that prisoners are innately bad guys. Because they have committed crimes, they have no credibility. The C.O.s retaliation is warranted—that is what came across to me. An eye for an eye, and damn, if you poke out one eye, we’ll poke out 100.

This is not, mind, you, justification for the any C.O. beating and yes, it should be addressed, but instead the DOC response led to what the online zine, The Appeal, called “collective punishment“ at the prison

This attitude toward prisoners by the DOC was shown today very clearly in a tense exchange with Attorney Lisa Kavanaugh, Innocence Program Director for the Committee for Public Counsel Services (CPCS). Attorney Kavanaugh had criticized the DOC’s non-contact visits for lawyers and their clients which took place in cubbies (during the lockdown), i.e. no privacy and all conversations can be overheard. This was the prevailing practice instead of contact visits in private rooms with doors (of which there are 3 at Souza) during the lockdown. Lawyers prefer private rooms because the material they discuss with clients is not material they want to be overheard by guards or anyone else, for that matter. The problem of prisoners having their legal paperwork removed and not having access to their lawyers during the lockdown is all part of what led CPCS and the Massachusetts Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers (MACDL) to file a lawsuit. They allegied a denial of access to counsel could harm prisoners and are seeking a temporary injunction forcing the DOC “to seek court approval if future limits on attorney/prisoner phone calls last longer than 48 hours.”

In the Feb. 19 courtroom during the temporary injunction hearing, the terse exchange spiked when one of the the DOC lawyers asked Kavanaugh if she had discussed her concerns about the visits with the DOC immediately after the lockdown. When she said she had not, the attorney said a bit sarcastically, “Were you aware there were security concerns?”

“I was aware my client was housed in a different part of the prison from where that happened?” Kavanaugh said forecefully,

“You’re not a security expert, are you?”

“No, I am not.”

“Do you believe everything a client tells you?”

I believe everything credible they tell me, yes.”

And there you have it. The DOC’s position on the men who they are supposed to protect and care for. They are not to be believed. However, the good news is that the other side of the story was on full display at the hearing, forttified by two very believable witnesses who were habed in from their Souza cells in cuffs.

Robert Silva-Prentice’s head and dreads that were ripped from his head. Photo courtesy of Attorney Patty DeJeuneas

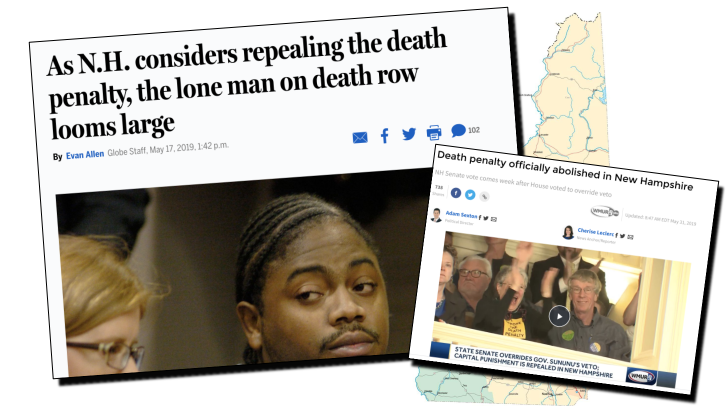

Robert Silva Prentice, the first of the two prisoners to testify was part of he other version of this story revealed on Feb. 19th. It is part of the story told by attorneys who have had more than 90 complaints from prisoners after correction officers retaliated for the violence in a brief two weeks.

Silva-Prenitice recounted that on January 22nd, he was taken out of his cell at 10am by the tactical team, who told him to strip to his boxers and tee shirt. He was taken to the gym, lined up with others, told to put his hands behind his back and handcuffed for two hours straight. He felt terrified with the guns (tasers which look like guns) pointed at his back. “It was like a movie,” he said, afraid he would “get shot,” and it was”degrading.” He was eventually placed in a different cell with a different cellie who said a few things about it being a “shit cell,” and then he recounted how the cell was stormed by 15 or so of the tactical team who “grabbed him” off the top bunk, threw him on the floor, tased him 5 or 6 times, yanked out some of his dreads. He saw his cellmate being assaulted. No photos were taken of these injuries, he recounted, until a lawyer got there, he said. He couldn’t see a nurse until January 28th, six days after the incident. When he got his legal papers back, they were not in the condition he’d had left them in, out of order and almost impossible to arrange by date.

“Would it surprise you” the DOC lawyer asked him, and she used this tactic over and over, “to learn that officers said you assauted someone?” By the way, no officers testified on Feb. 19th that he indeed did assault anyone.

The plaintiffs also included Carl Larocque and Tamik Kirkland but they did not appear at the hearing. The second prisoner to testify was Ricardo Arias. Arias told a similar tale of abuse from the guards, recounting how he, too, was brought in his underwear to a different location. He said he saw people get tased and maced. He was quite sure that no one brought cameras into his cell to video him (although the DOC said they had 40 to 50 hours of videotape). Most upsetting to Arias was that he had been using the law library and taking a large role in his appeal, and law library use was forbidden during the lockdown since they were locked in their cells (without showers for 72 hours). He did not get his legal work back until Feb, 14, and said, without those papers he felt he could not do his part “in fighting for my life.” He also felt a great hardship in not being able to talk to his attorney.

“The right to counsel is really the basis of our argument‚” Victoria Kelleher, president of MACDL said after Wednesday’s hearing. “People do have a right to counsel, a right to effective representation, and we can’t possibly do our jobs if we can’t see and speak to our clients.”

In the closing arguments CPCS Attorney Rebecca Jacobstein said the DOC justified their actions based on “a secret disorder policy” that is not available by public records and which they say can go into effect after something is declared an emergency, if conditions are severe enough as judged by the DOC. She said the lawsuit had a “positive impact” on helping prisoners get their rights back and the injunction was absolutely needed to make sure this did not happen again. In terms of the loss of paperwork for the prisoners, “Every day a brief is not filed is another day spent in jail and yes, it has harmed the prisoners.” She also said “The unchecked denial of constitutional rights is an exaggerated response.”

Robert Silva-Prentice said having an attorney gives him “hope.” And Ricardo Arias said the urgency created by this lockdown was palpable: “My life is on the line.”

Picture of the Suffolk Courtroom with Judge Beverly Cannone presiding as Superintendent Stephen Kenneway takes the stand for the DOC rebuttal.

The DOC’s main argument is that the lawsuit is “moot.” Everything is “status quo.”

Jacob Cote from MassLive said legislators who visited the prison after the lockdown “raised concerns about the safety, hygiene and health of prisoners.” Some of those who made unannounced visits, allowed by legislators, included Sen. James Eldridge, Rep. Lindsay Sabadosa, Rep. Mike Connolly, Rep. Mary Keefe, Sen. Patricia Jehlen, Rep. Tram Ngyen, and Rep. Chynah Tyler. They saw such abuses as blood in prisoners’ rooms and “unknown liquids on the floor. [Sabadosa] also heard a report of an epileptic prisoner who was resting on the top of a bunkbed in his cell when he had a seizure, fell off bed and laid in his own blood for an extended period of time,” wrote Cote.

Judge Cannonne said at the end of the day she would take all into advisement.

But from my way of thinking, the fisco at Souza is a story that echos from what we have heard from prisons across the country in these terrible times.

_____________________________________________________________________________

STATEMENT FROM ATT. PATTY DEJEUNEAS WHO REPRESENTS ROBERT SILVA-PRENTICE.

Yesterday, Superintendent Kenneway, in a blatant act of witness intimidation and retaliation, threatened to take disciplinary action against my client, 22-year old Robert Silva-Prentice. The threat came only after Mr. Silva-Prentice exercised his First Amendment right of petition by filing grievances about the brutal assault he suffered at the hands of DOC staff; after he filed a civil complaint against Kenneway and other high-ranking DOC officials; and after Mr. Silva-Prentice testified openly, honestly, and credibly about what happened to him at Souza-Baranowski on January 22, 2020.

Kenneway’s threat was based on the fictitious notion that my client, who weighs 145 pounds at most, assaulted armed members of the DOC’s paramilitary tactical teams. Had DOC complied with its own regulations, they would have taken photographs of his injuries. He has at least four distinct sets of taser burns — and their position shows that the tactical team tased him at least four times while he was laying on the floor, stomach down, with his hands cuffed behind his back. They also pulled a clump of dreadlocks from the back of his head.

Simply put, it is ludicrous for Mr. Kenneway to try to justify the extreme brutality against my client by saying that he was the attacker.

_____________