Judge Joseph Dever, center, featured with me and our Changing Lives Through Literature class

My dear friend and colleague, Judge Joseph Dever, is in hospice care at home and not expected to live past the weekend. I have never eulogized someone before their death, but Joe and I often joked that he was essentially “my second husband,” and I know he needs to feel my words sent into the world at a time when he is dying.

I worked with Joe beginning in 1992 when together we started the Changing Lives Through Literature (CLTL) program for women. We were inspired by Judge Robert Kane and Professor Robert Waxler who began the program for men in the southern part of Massachusetts. They aimed for an opportunity to help people get out of the cycle of crime by offering them a literature intervention, so to speak. We wanted to give it a shot with women, and so for nearly twenty-three years, Judge D, as I called him in our classes, trooped from Lynn to Lowell every other Tuesday evening for CLTL at Middlesex Community College where we held classes, most often in the president’s office. For twenty-three years, he joyfully climbed into a van with the women and a Lynn probation officer, and rode more than thirty miles to and from the college, because he believed so strongly in this program

I have written many times about CLTL, notably here, but for those who don’t know, the program brings those sentenced by the court to probation into a college literature seminar. It is a very unique collaboration between the courts and education, and while “changing lives” is a large claim, it certainly helps pave the road to new attitudes, abilities, understandings, and intentions—for all the participants. Simply put, probationers, probation officers, judges, and professors sit in a classroom together and discuss books. I call it a “democratic classroom” because all opinions about literature are on equal footing. It’s been called everything from “Books for Crooks” to a program where they “Throw the Book at Them.” Judge Dever always called it “the joy of my judgeship.”

Joe Dever was Boston born and graduated from Boston University School of Law in 1960. He was first a dedicated public defender, something he prided fiercely, and he always told me, “in no uncertain terms:” There are no better public defender programs in any part of the country than in Massachusetts. He loved the law passionately, almost as much as he loved his family. Joe and his wife Anne (who always organized and appreciated Joe’s lofty spirit) raised a family of public servants. They inspired their four children to fight for the good of others. They relished humor, and they loved their home in Marblehead. A loyal and generous soul, Joe spent many mornings with buddies from his town, eating breakfast, discussing the day, admonishing the Red Sox, and critiquing all decisions made by those in public office.

But Joe knew the law was a foundation for him. Once when I was called for jury duty, Joe told me he hoped very much that I’d make the cut. “Nothing teaches you more about being a citizen than being on a jury,” he said.

Like his uncles, Governor of Massachusetts, Paul A. Dever, and Ted Dever, the presiding justice at Cambridge District Court, Joe yearned to make a difference. He was appointed a judgeship in 1987 by Governor Michael S. Dukakis. He was eventually appointed presiding justice in the Lynn District Court and held that position for more than 10 years.

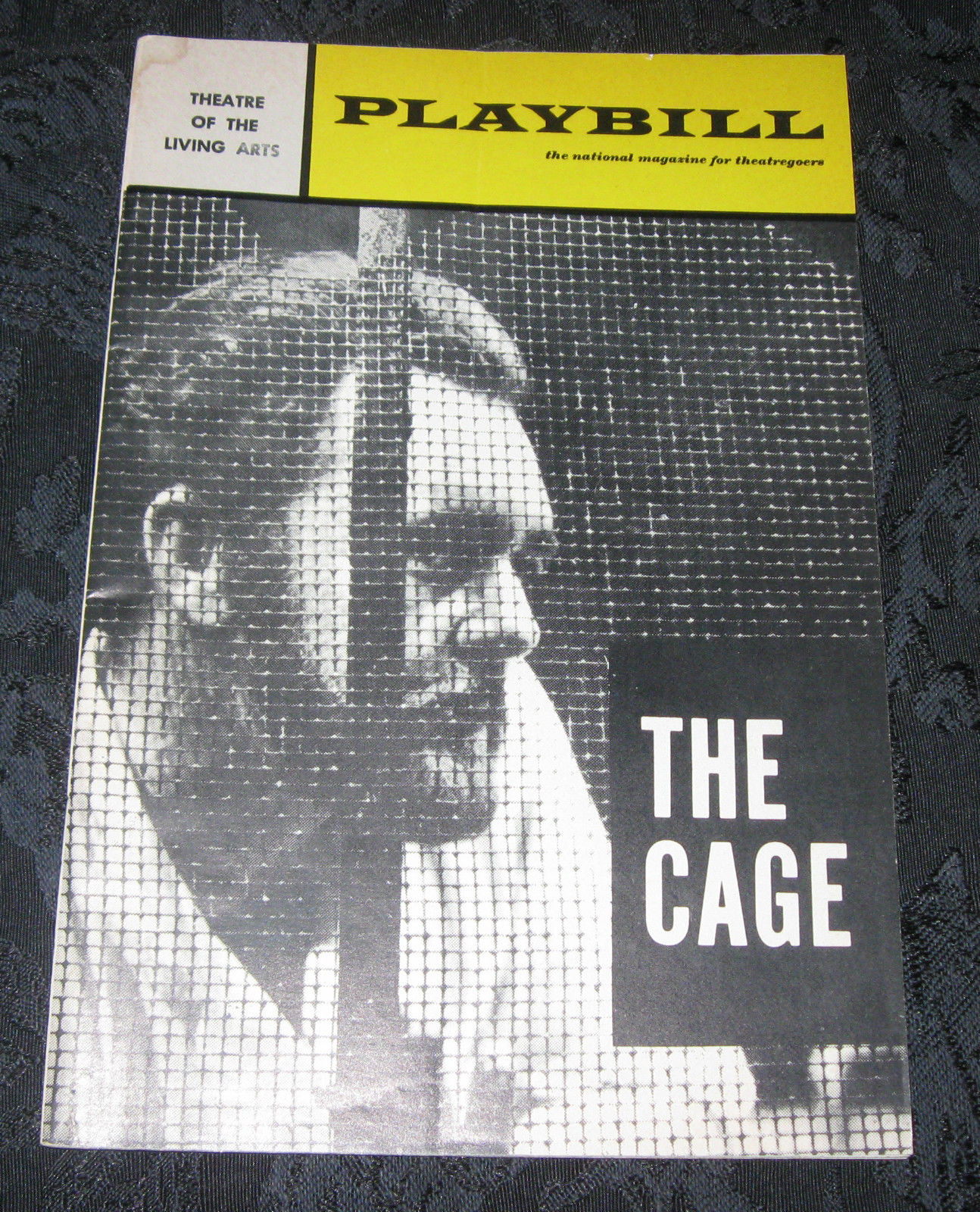

A 2005 Boston.com article written by Kathy McCabe about Judge D. when he retired from the bench at age 70 (as is required by law) quoted him as saying “My mother believed very much in the dramatic arts.” That is another thing Joe and I shared, a love for the spoken word. After my book Shakespeare Behind Bars came out, Joe stood on the bench in his robes at our graduation ceremony and read from my book to a packed Lynn District Court, quoting me and quoting Shakespeare.

There was no one who could read like Joe. Every semester at the beginning of our CLTL class, Joe read the poem I have on my syllabus from Barbara Helfgott Hyett’s book, In Evidence. Helfgott-Hyett interviewed veterans, soldiers who served in WW II, to create her Holocaust poetry, and after the reading, the class discussed what one has to know in order to understand this poem—what words, phrases, ideas. Joe’s voice always rang out with the same kind of pain and joy that he contained in all his conversation. A sonorous voice filled with the kind of wisdom and understanding of a life well lived, a life that indeed filled a room.

At the University Theatre

in Harvard Square, I went

to see The True Glory and

I was still in uniform.

When they showed the films

of Dachau, the woman who sat

beside me said, “That’s a lie.”

I was rugged in those days.

I just couldn’t take it.

I said, “Lady I’ve been there.

I still smell the stench.”

And I said it loud and all

the people heard.

Joe’s life was a tribute to language. He lived with dignity, joy, a gratitude for all that he had, and the knowledge that he did change people’s lives. He will be sorely missed by the world. I am proud to say I shared so much of my work with Joe Dever, and to Joe, I say yes, “all the people heard.”