This is from Hannah who was incarcerated in Texas.

Addiction is a disease – and yes, it is a disease – that is met with judgment and intolerance instead of compassion and understanding. It is the only disease I can think of that is actually criminalized.

I have lost so many loved ones – good people – to this affliction, and I can’t help but blame this stigma for some of that. I have heard people say that even if they overdose, they don’t want 911 called. They are scared to ask their families for help due to fear of judgment and anger. They refuse to go to the hospital for life-threatening infections due to the backlash and patronization they will surely receive from doctors and nurses.

I didn’t used to believe this was a disease. I thought that was a cop-out. I now know that it is. Addicts don’t want to be drug addicts. They don’t want to spend all of their money, face homelessness, lose their families and friends, their freedom, and possibly even their life. I can remember times I would sit in my bathroom or closet, spending hours futilely looking for a vein, as tears streamed down my face. I didn’t want to be doing that, no addict does, but I couldn’t stop. I wasn’t even getting high anymore, only maintaining, but I still couldn’t stop. Drug addiction is such a sad, lonely existence, and nobody wants that life.

I was fortunate to have a family that cared enough, and had the resources to send me to one treatment center after another to try to help me. I ultimately went to a total of 8 rehabs and numerous other detox centers. I tried medication-based treatment, and Twelve Step groups, but nothing worked.

While I was there, I met other women (and men) who turned to drugs because life became too much to bear. They did it to escape, at first, but eventually found they were unable to stop. These were good people, with loving friends and family, who simply didn’t know how to cope with a variety of issues, including, but not limited to: childhood abuse, sexual molestation, death of a child, adoption, and co-occurring mental illnesses. Those are just a few of the things that I, personally, was trying to numb out.

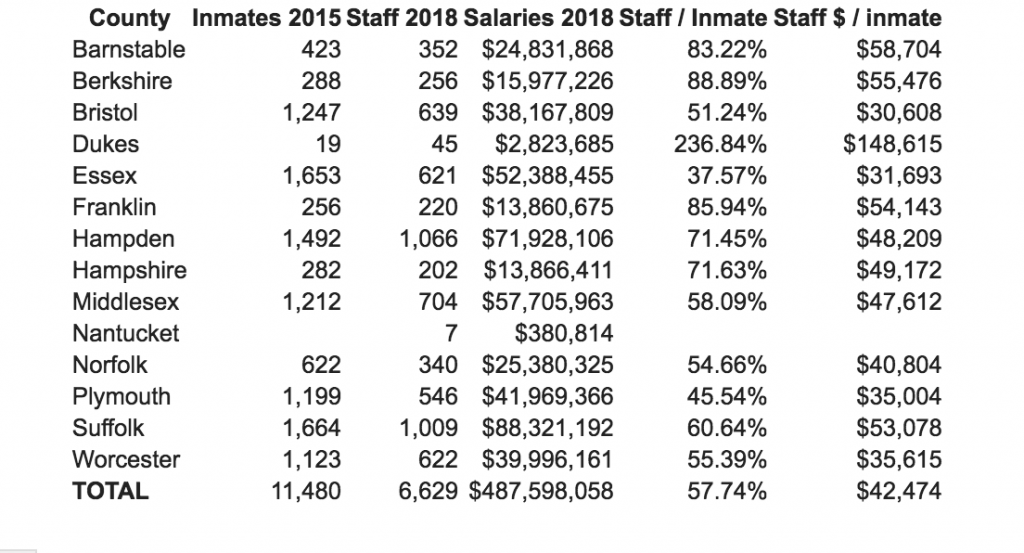

I spent 16 months in county jail and state prison for nothing more than drug possession. When people think of prison, they tend to think of rapists and murderers, but I can tell you from experience that those are the minority. Most people are in for drug-related offenses. They are incarcerated in hot, non-air conditioned prisons throughout the Texas summers. Temperatures inside are easily higher than 100 degrees, and it becomes difficult to breathe. The guards treat inmates like dirt, simply because they can. Their human rights cease to exist. At this point, they are no longer considered human, but instead “state property.”

I have since turned my life around. I am no longer addicted to drugs. I have a decent job, a nice place to live, bills to pay, and responsibilities I am able to stick to. I am one of the lucky ones.

However, because of my past, I will always be judged. My “criminal” history will never leave me. I will forever have trouble finding jobs, housing, credit, etc.

Just this past weekend, I applied for a volunteer opportunity to help children who are struggling with some of the same issues I have faced – children who will almost certainly attempt to self-medicate at some point in their lives. I thought I had something to offer, and I was excited to be a part of this. I was approved and ready to go, until they ran a background check at the last minute. At that point, I was turned away. People told me this would happen, and it’s something I live in fear of every day.

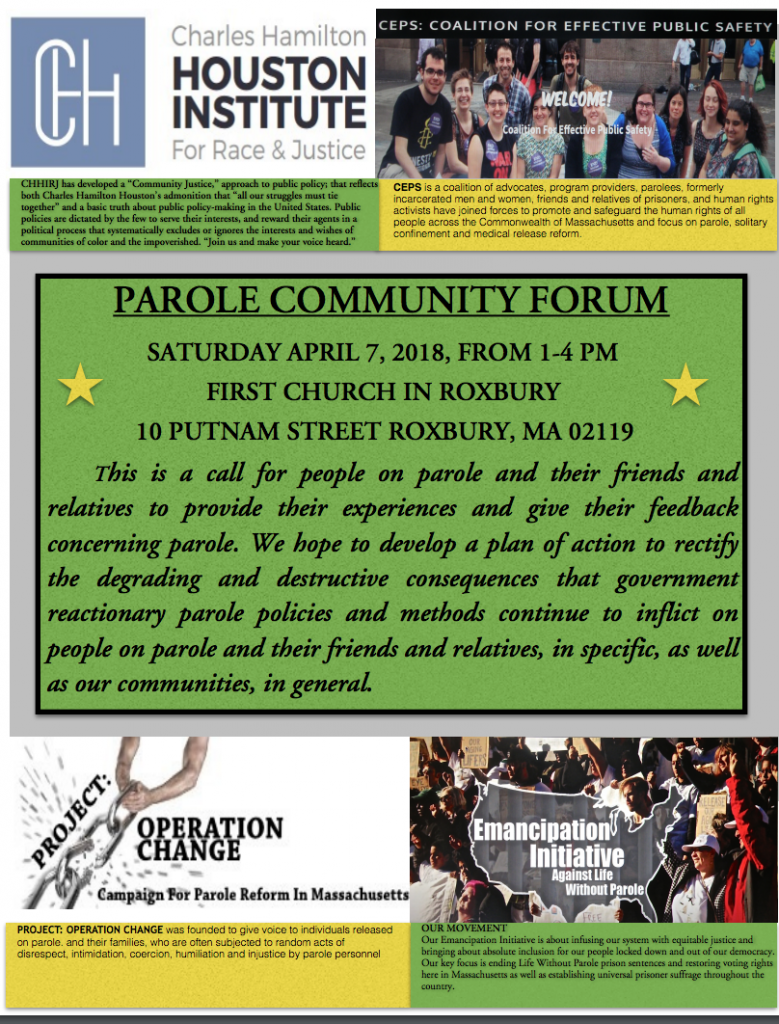

People wonder why recidivism rates are so staggeringly high. Why people who are released from prison go right back to the same behaviors that got them in trouble. This is why. There is no hope for us who have been convicted of a crime, even a non-violent one. We are branded forever with a scarlett letter, of sorts. There is no incentive not to commit more crime. Once you have one felony, in this country, you really might as well have ten. It becomes too difficult to get a legit job and to make clean money, so it becomes almost necessary to get back into the dope game or illegal activity just to support our families.

People often say, “don’t do the crime if you can’t do the time.” Well, I did the time. I’ve paid my debts. So why can’t people just drop it already? Why can’t we leave it in the past?

To put it into perspective, my first offer from the prosecutor in my case, was 5 years in state prison. I would have been better off, legally speaking, had I stolen a car, assaulted someone, committed certain sex offenses, or put people’s lives at risk by driving drunk. I have always adhered to a certain moral code, even in my addiction. There were things I just wouldn’t do. I refused to share drug paraphernalia, steal, or sell my body. But according to the law, I would have been better off doing those things than committing the crime I was charged with, even though the only victim in my case, was me.